The linear motor used in this generation of pumps has key advantages over a 3-phase AC motor. The most significant point of difference between the two drive technologies is the concept underlying the motor. Whereas a 3-phase AC motor provides rotational motion that has to be laboriously converted into oscillating motion, the way a linear motor works is naturally oscillatory. This has major implications for the construction of the metering pump, because a linear motor eliminates all the mechanical transmission components and adjusting eccentrics that allow stroke lengths to be set. Micro-metering pumps with linear motors can therefore have a significantly more compact design. In addition they are less subject to wear, since fewer moving parts are involved. As a result, they are impressively low-maintenance. The stroke lengths are set electronically and applied by means of control electronics. This is much more precise and reproducible than using a manual adjustment wheel.

Individual metering profiles

Linear drives are direct drives. This means that their motion profiles are controlled by software and then transferred to the linear motor by means of programmable logic controllers, for example, or electronic control technology. This provides the opportunity to program any number of metering profiles. It goes far beyond the bounds of what can be achieved with pumps driven by 3-phase AC motors.

It is true that with the latest generations of traditional metering pumps, it is sometimes possible to generate asymmetric suction and pressure metering profiles. Nonetheless, and despite painstakingly integrated crank mechanisms, vector control and variable frequency drives, the degrees of freedom are severely limited. Where highly precise metering of a variety of fluids is required, with individual flow curves and different processing parameters, linear metering pumps are in a class of their own.

Two practical examples illustrate this unique position: the metering of additives and reagents in chemical processes requires a high degree of precision. Often at the level of a laboratory or pilot-plant, absolutely zero spillage is also a requirement. In addition, to control the chemical or physical processes accurately, cycles of constantly variable duration are required.

In a laboratory system for metering a viscous fluid, a four-stage metering profile with a linear pump was deployed:

- Phase 1: Discharge stroke and metering: in order to open all valves on the metering side simultaneously and set the fluid in motion, the process starts at high speed.

- Phase 2: After a short period, the speed is reduced and maintained at a constant level. This allows the fluid to be metered continuously.

- Phase 3: The slight reduction in speed prevents spillage.

- Phase 4: This is followed by a short suction process and the transition to the next discharge stroke.

Gas odorisation

The metering task when odorising natural gas or hydrogen is quite different. These gases are odourless by nature but are highly dangerous due to their flammability. Chemicals with powerful odours are therefore mixed into them so that any leaks in the pipework can be detected as quickly as possible. Substances regularly used include tetrahydrothiophene (THT) and mercaptans as well as some sulphur-free compounds. The metering of these substances needs to be as continuous as possible because this is the only way of ensuring broadly homogeneous distribution in the gas flow. Depending on the odorant involved, metered metering flows will be between 3 and 10 mg/m³. In these cases, the metering profile is characterised by a short suction stroke (< 0.5 sec) and a long, even discharge stroke (up to 30 sec).

The odorising systems developed by Honeywell Gas Technologies use linear motor pump technology. They are low-maintenance and virtually self-venting. Due to the space saving design of linear motor pumps, it is even possible to equip a system with several of them so that backup or parallel operation is possible if required.

Micro-metering in the desert

Micro-metering pumps with linear motors have further features that come into play with standalone equipment responsible for the metering of anti-corrosion agents or odorants in pipelines. Since such equipment is mostly located in the middle of the desert, far from civilisation, reliability and low maintenance are essential. Photovoltaic systems are generally responsible for supplying the power. The DC electricity produced by the semiconductor elements drives the linear motor pumps directly. Frequency converters are unnecessary. If such systems are fitted with a web-enabled control system, they can be monitored and controlled entirely remotely. Diagnostics, amendments to parameters and uploads of new functional software are all possible without the need for anyone to be present on site. For standalone equipment in remote locations, this is an extremely important benefit.

Many users do not know exactly what their operating parameters are, or else the parameters keep changing because metering systems are used in various different processes. In such cases pump systems with a high degree of flexibility are needed. This is one of the key strengths of linear pump technology. With this technology, a highly dynamic process involving 200 strokes per minute can be configured as accurately as metering with just one stroke for 30 seconds. In a two-stage, stable-pressure operation, this allows such equipment to be used across a wide range of operating pressures from 5 to 260 bar (design: 400 bar). Depending on the pump model, pump capacities are spread across a range from 0.01 l/h to 20 l/h. Three different control types are possible here: stroke or frequency control, stroke and frequency control, and stroke and frequency control including preset motion profiles. “With this new linear motor pump technology, the focus in discussions with customers has completely changed,” says Bernd Freissler, Product Manager at Prominent GmbH, reporting on his experience. “We used to get asked: ‘What can your pump do?’ Nowadays the prime question is: ‘What metering profile will yield the best outcome in my process?’ That’s what the universal adjustability of the linear motor metering pump offers.”

Oscillation as the drive principle

On all metering pump systems fitted with 3-phase AC motors, rotational motion has to be converted into oscillating motion. This is achieved by the use of appropriately designed gear reduction ratio equipment, which converts the rotational speed of the motor into a stroke rate. The precise stroke or metering volume is usually set by means of a crank mechanism with an adjusting eccentric, using a manual adjustment wheel.

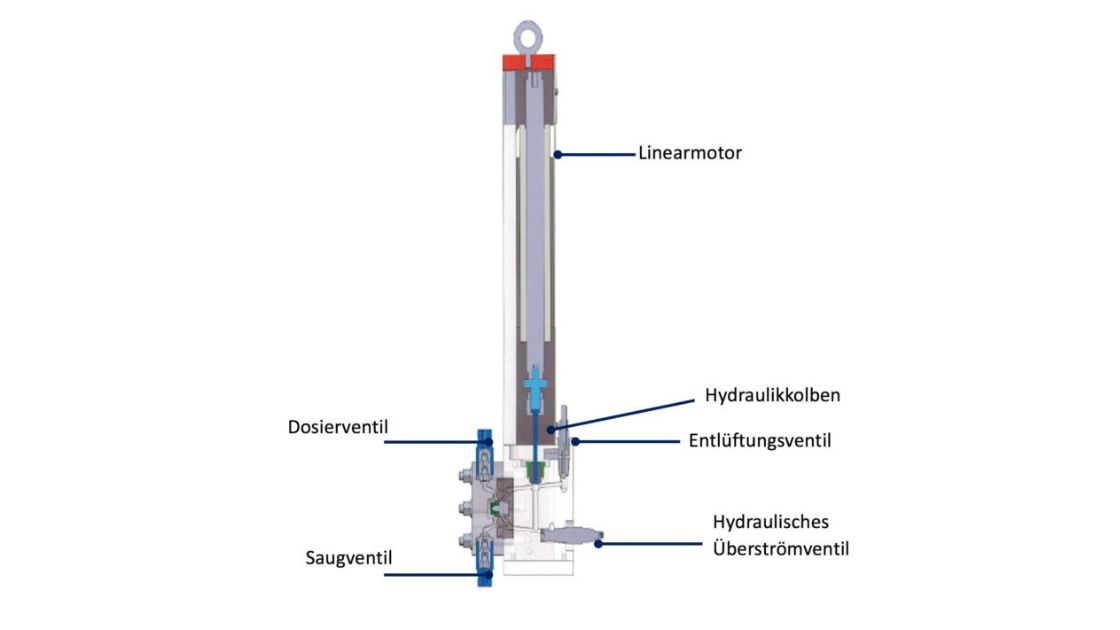

Prominent GmbH takes a new approach. The company fits its micro-metering pumps with a linear motor. Motors of this type are direct drives which inherently provide oscillating motion. This eliminates the entire mechanism of transmission gearing and adjusting eccentrics. The system is characterised by a high degree of dynamism and precision, and by unrestricted flexibility with regard to the achievable flow curves. With no conversion or transmission tolerances of any kind, individual metering curves can be programmed.

Conventional rotating asynchronous or synchronous motors generate the magnetic field by means of orbitally offset coil windings (stator), which the rotor follows with its permanent solenoids. In linear motors, on the other hand, the coils are arranged on a flat track. Here, the armature fitted with a permanent solenoid follows the offset coils of the stator. This results in an oscillating travelling field by purely electrical means. The length of the stator with its coils and pairs of solenoids is proportionate to its propulsive power. Across the entire length of the package, a constant force is available in both directions. The key benefits of the linear motor can therefore be summed up as follows:

- The direct drive allows any number of metering profiles to be programmed.

- The gearless construction is low-maintenance, virtually free from wear, compact and space saving.

- Its highly dynamic nature balances out inaccuracies in the hydraulics – in valves, for example.